Here’s a bit I cut out of a very early draft of Talio’s Codex. Note that in the version Dovuta is the one accused of murder, ‘Magistrate Jilani’ is ‘Magistrate Palane,’ and ‘source and return gutters’ are ‘service and utility gutters.’ Lots of non-canon things in this excerpt.

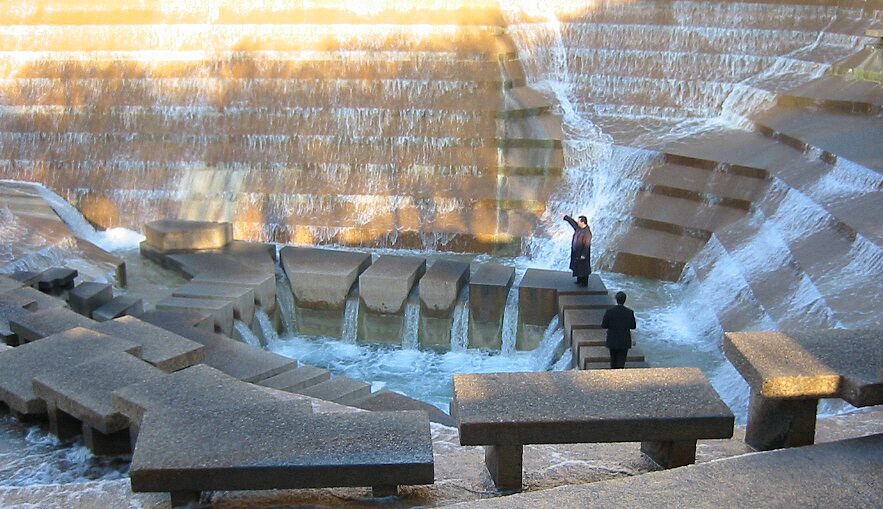

This scene was intended as worldbuilding to build out the city’s canal/water supply concepts. I had some vague idea that the southern exchange would be something like the fountains in the conclusion of 1976’s Logan’s Run.

“And then what happened?” Vinne asked.

“And then, she went back to our desk and lied and swore that she did not know Selig and had never known him.” Talio shrugged as best as he could given the load he was carrying.

“Did you tell the magistrate?”

“Tell him what? That I thought she was lying? That would be a supposition on my part, not fact. Unless Dovuta told me, or I had concrete evidence to bring forward, I had no choice but to let her say what she wanted.” Talio sighed. “The prosecutor accepted it, and stuck to safe questions after that. And when it was my turn to question her, I also remained in the realm of safe questions. Everything was very, very safe.”

He stumbled, and the large bag they were holding fell to the cobbled street. “Watch where you are going,” Vinne said. Talio still could not believe that they were in fact on their current mission.

He’d returned to the Double Moon Inn that evening in a poor mood, and when he’d decided to take a nap before seeking some dinner, he’d smelled the staleness of the sheets. Vinne had thrown up his hands and said that he had no clean ones.

“Then let us find a laundry woman,” Talio said. “Your clothes could also use a wash.”

Vinne was about to object, but he sniffed at himself under his arms and shrugged. “They don’t come to the quarter anymore. Not enough business.”

“I can’t sleep on that bed,” Talio said.

Vinne walked over to the little rug and pushed it aside, leaning down to pull up the trapdoor to the gutters. Talio slammed the trapdoor back down with his foot. “You are not going to wash the sheets in the utility gutter. It’s filthy.”

Vinne simply raised his eyebrows at him. “No,” Talio said. “I won’t let you use the service gutter either.” It was unthinkable, not to mention highly illegal. “It’s a capital crime. Were you aware of that?” He thought back to one of the memorable hearings he’d had in his first year: a young man who’d decided for some reason to bathe in a service basin. Scodel’s laws was clear on the crime; the man was guilty of a bodily offense against the state. Talio had searched through the maze of sentencing rules and guidelines at the back at the codex, but the lightest sentence he could find was a caning. Unbelievably, one of the possibilities was a public whipping.

“Then let’s go to the southern exchange,” Vinne said with a sly smile. “I can pick up some wine while we’re out.” He was going through at least one bottle a night, by Talio’s estimate. It was not for him to judge or control the innkeeper’s drinking – what could he do, restrain him physically?

Talio hadn’t wanted to go to the southern exchange; he hadn’t been since he was a youth. There was something vaguely unsavory about the area. But they would have to drag the laundry out of the quarter regardless of whether they sought out the exchange or a washerwoman. And with the quarter being so downstream, they were closer to the exchange….and it was free.

So that evening found him and Vinne carrying a large sack of laundry from the inn containing his bedsheets, some spare sheets from storage, towels and other cleaning cloths. Vinne hadn’t drank as much as usual so far, but he weaved a zigzag pattern back and forth across the street, forcing Talio to stumble after him. At one point, he had to pull Vinne back from the edge of the canal lest he – and the sack – fall in.

The exchange was in the southernmost part of the city, a reservoir with high walls and the thundering sound of waters collecting from various gutters and pipes. Here, all of the service water collected, to be returned back upstream as utility water.

Talio had heard that decades ago, the southern exchange had filtered the incoming service water before turning it back through the utility channels, but that was no longer being done. At the northern exchange, the utility water was properly filtered, cleansed and blessed before it came back down as the service water, but the southern exchange served more as a waystation. And a gathering area.

The poor, the homeless and those who did not have access to the water streams for other reasons gathered at the southern exchange. On this warm summer night, there were dozens of men, women and children bathing and washing themselves and their possessions. Talio was sure that at least a few were also drinking from the reservoir, though he didn’t want to contemplate it. Of interest, he noted that there were no Incarnites that he could see.

Vinne and Talio brought the sack to the edge of the reservoir, and Talio started handing Vinne its contents one by one. The innkeeper had brought a precious sliver of soap from the inn, and he scrubbed at the sheets in the water while a toothless old woman with her own laundry watched them enviously in the fading light. “What will happen at the hearing tomorrow?” Vinne asked.

Talio withdrew one of Vinne’s undergarments and wrinkled his nose. “Pazli – the Incarnite – was supposed to be questioned. He is the only other person who was at the manse that day.” He handed the bundle to Vinne. “But tomorrow is an Incarnite day of worship. Did you know that?”

Vinne shook his head and bent to his task. “Magistrate Palane has delayed the hearing by a day,” Talio said. “He’s the last non-expert witness.”

“Do you think he might have done it? Killed Selig.”

“No,” Talio said with a shake of his head. “But I have to be thorough.”

There was more than that, of course. If he could redirect suspicion from Dovuta, perhaps that would help her case. She was a noblewoman, true, but the prosecutor’s repeated questions about her knowing Selig worried him. The prosecutor did not have any evidence to the contrary, or she would have had to have submitted it already. But that did not mean the evidence wasn’t out there waiting to be found.

The magistrate would not find the Incarnite guilty. Dovuta’s testimony clearly showed that he had never left the servant’s quarters, and Talio could not imagine that Pazli would incriminate himself by saying otherwise during his testimony.

Vinne handed back the washed undergarments and Talio started to fold them. He sighed. As a result of Dovuta’s threat, he was deliberately ignoring how guilty she seemed. Worse, he was now considering throwing suspicion onto an innocent man. As a magistrate he had tried to follow the principles of justice, but as a private defender, his primary duty was to clear Lady Dovuta Balsamo, as long as there was a reasonable doubt in his mind that she was guilty. But what was reasonable about Dovuta?

They placed the wet folded laundry back into the sack and started dragging it back home. Vinne was becoming restless, and Talio imagined he was overdue for some wine. That meant that he would have to hang the laundry up for drying once they returned to the inn.